Browse all resources

Filter By:

Self-Reported Suicidal Behavior and Past-Year Substance Use Disorder, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table: 6.87B

Self-Reported Suicidal Behavior and Past-Year Serious Psychological Distress, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table: 6.87B

Self-Reported Suicidal Behavior and Past-Year Major Depressive Episode, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table: 6.87B

Suicide Deaths by Drug Poisoning, 2023

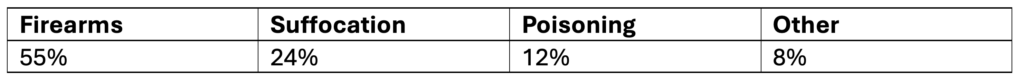

Suicide Deaths by Means

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Injury Outcome: FatalInjury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: All Ages

Sexes: All Sexes

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

MCD – ICD-10 Codes: T40.1 (Heroin); T40.0, T40.2, T40.3 (Opium, Methadone, Other opioids); T40.4 (Other synthetic narcotics); T40.5 (Cocaine), T42.4 (Benzodiazepines); T43.6 (Psychostimulants with abuse potential)

AND

X60-X84 (Intentional sel-harm)

Year/Month: 2023

Group By: Year

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Selected Injury-Related Death Rates, 2014-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: V01-V99 (Transport accidents); X40 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics); x41 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotice, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified); X42 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics [hallucinogens], not elsewhere classified); X43 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system); X44 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances); X45 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol); X46 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapours); X47 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapours); X48 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to pesticides); X49 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances); X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm); X85-Y09 (Assault)

Year/Month: 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: Year; ICD Sub-Chapter

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: V01-V99 (Transport accidents); X40 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics); x41 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotice, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified); X42 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics [hallucinogens], not elsewhere classified); X43 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system); X44 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances); X45 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol); X46 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapours); X47 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapours); X48 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to pesticides); X49 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances); X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm); X85-Y09 (Assault)

Group By: Year; ICD Sub-Chapter

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among High School Youth of More Than One Race in the U.S., 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Adults of More Than One Race in the U.S., 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.70B, 6.72B, & 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among People of More Than One Race in the U.S. by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

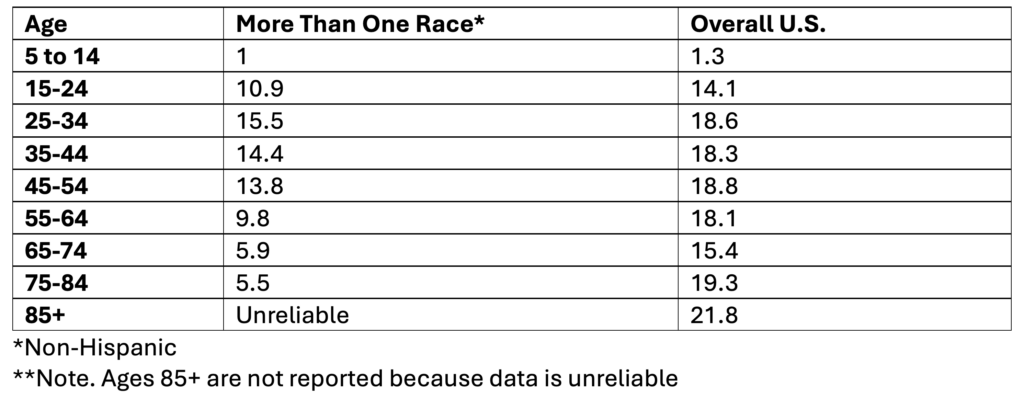

Suicide Rates Among People of More Than One Race in the U.S. by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among Multi-Racial People of More Than One Race in the U.S., 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among White High School Youth in the U.S., 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among White Adults in the U.S., 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B, 6.72B, 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among White People in the U.S. by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

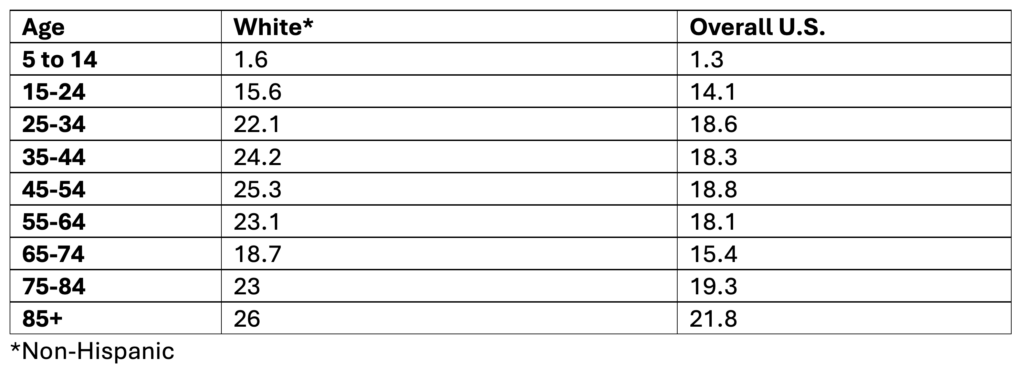

Suicide Rates Among White People in the U.S. by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among White People in the U.S., 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander High School Youth, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Adults, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B, 6.72B, & 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander People by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

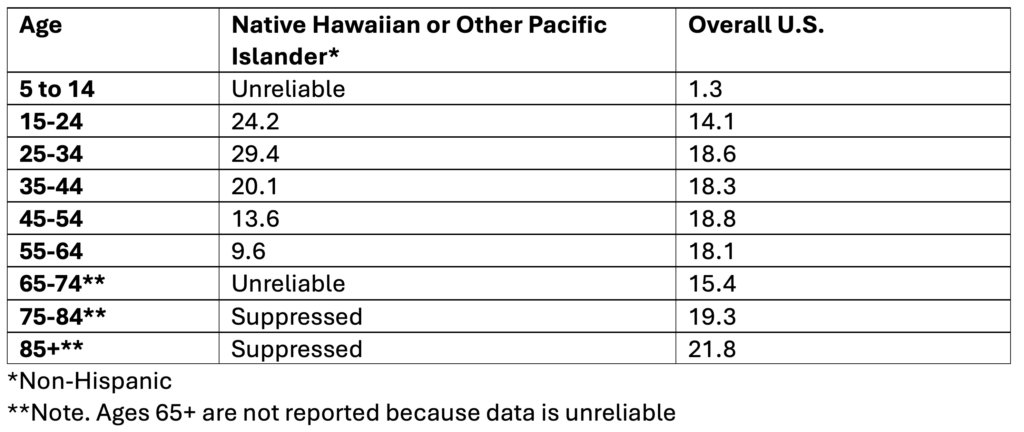

Suicide Rates Among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander People by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander People, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Hispanic or Latino High School Youth in the U.S., 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Hispanic or Latino Adults in the U.S., 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B, 6.72B, & 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among Hispanic or Latino People in the U.S. by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Hispanic Origin; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

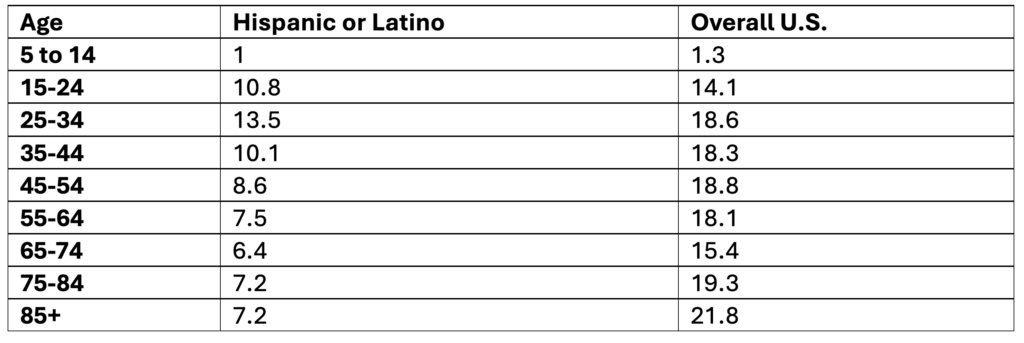

Suicide Rates Among Hispanic or Latino People in the U.S. by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Hispanic Origin; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among Hispanic or Latino People in the U.S., 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Black or African American High School Youth, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Black or African American Adults, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B, 6.72B, & 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among Black or African American People by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

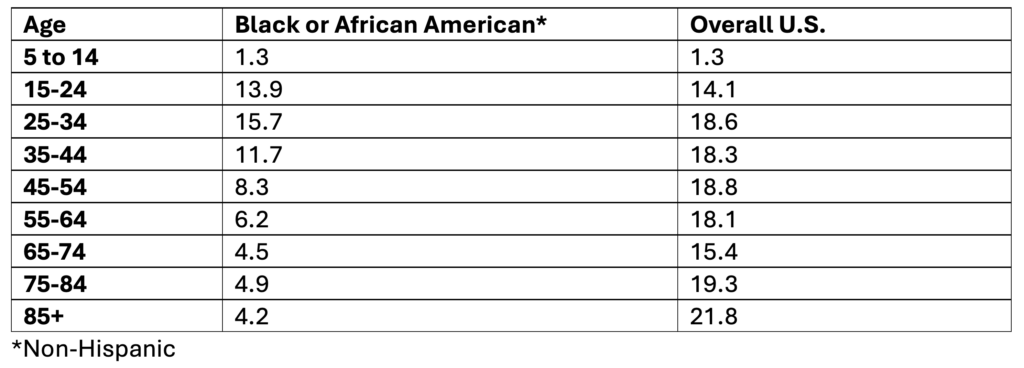

Suicide Rates Among Black or African American People by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among Black or African American People, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Asian High School Youth in the U.S., 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Asian Adults in the U.S., 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B, 6.72B, & 6.73B

Suicide Rates Among Asian People in the U.S. by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

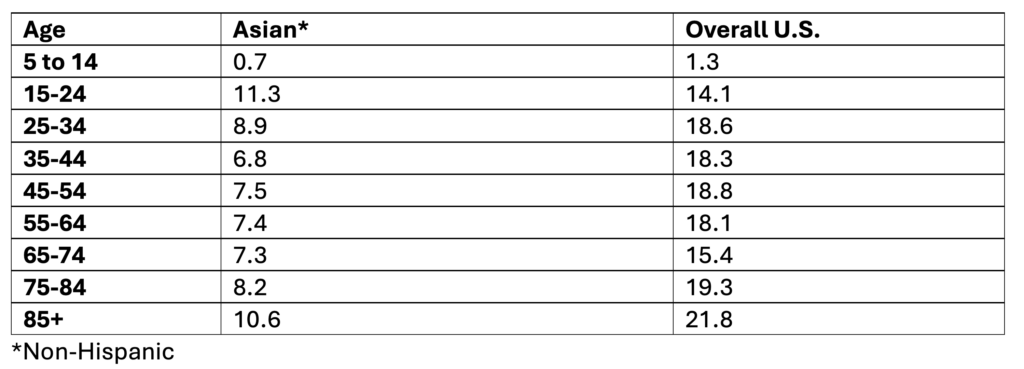

Suicide Rates Among Asian People in the U.S. by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates Among Asian People in the U.S., 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among American Indian and Alaska Native High School Youth, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among American Indian and Alaska Native Adults, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.72B, 6.73B, & 6.74B

Suicide Rates Among American Indian and Alaska Native People by Sex, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

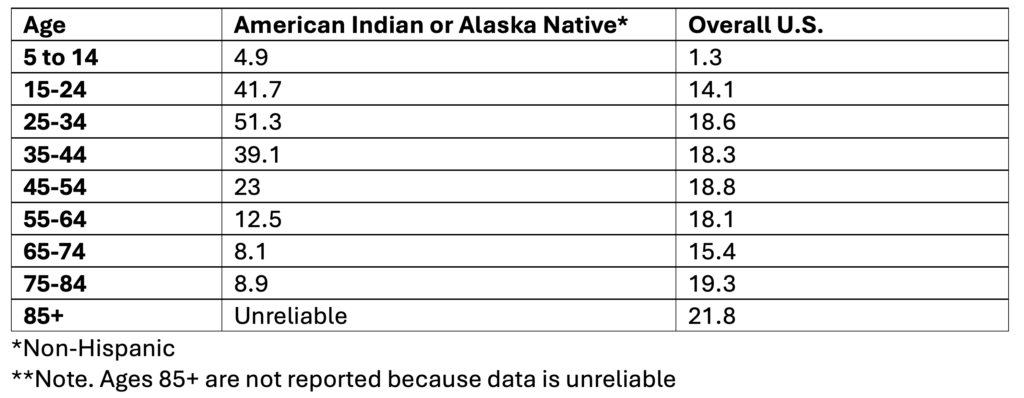

Suicide Rates Among American Indian and Alaska Native People by Age, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Single Race 6; Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

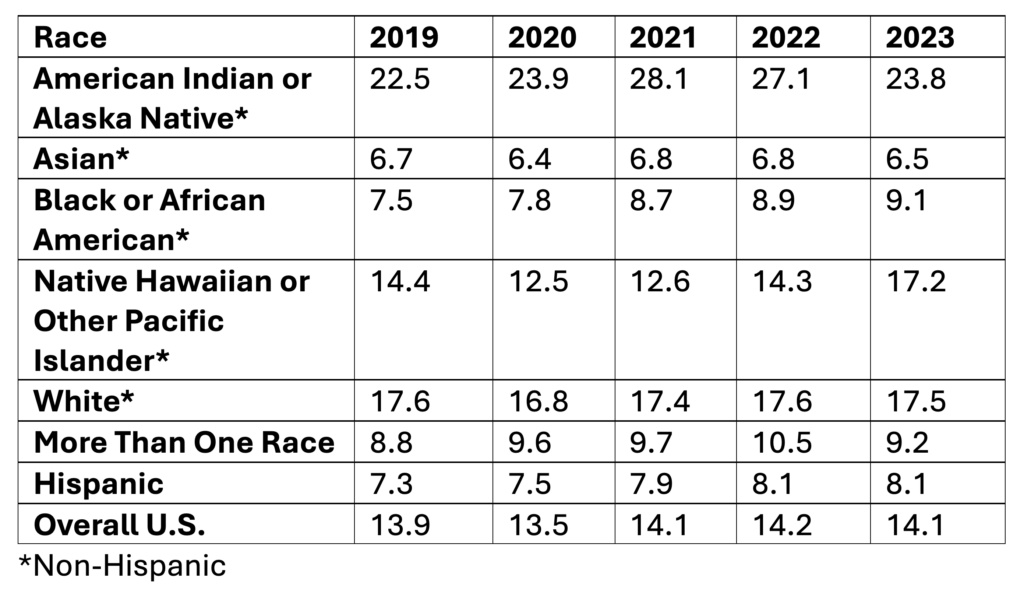

Suicide Rates Among American Indian and Alaska Native People, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

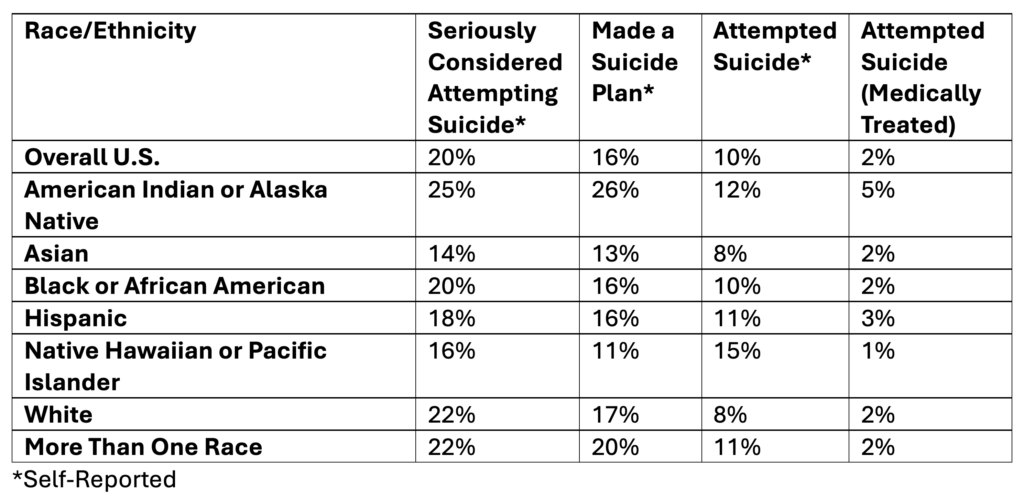

Past-Year Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among High School Youth, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

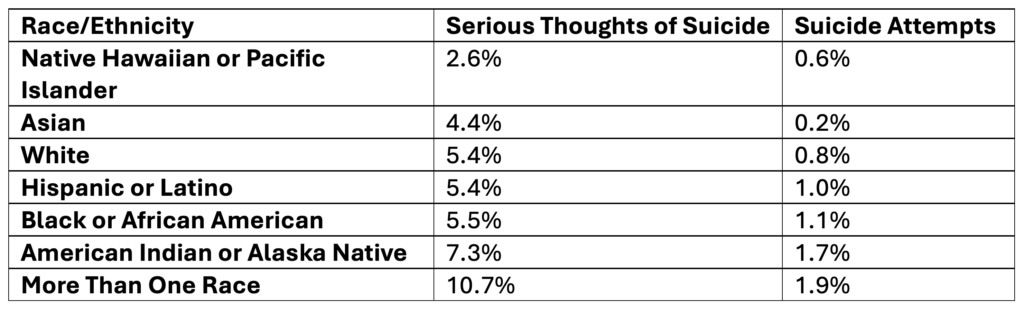

Past-Year Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Adults, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables: 6.71B & 6.73B

Rates of Suicide by Race/Ethnicity, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide by Means by Age Among Females, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Fatal Injury Reports

Injury Outcome: Fatal

Injury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: 15 to 19 through Unknown

Sex: Females

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Year and Race Options: 2018-2023 by Single Race

Suicide by Means by Age Among Males, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Fatal Injury Reports

Injury Outcome: Fatal

Injury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: 15 to 19 through Unknown

Sex: Males

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Year and Race Options: 2018-2023 by Single Race

Suicide by Means Among Females, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Fatal Injury Reports

Injury Outcome: Fatal

Injury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: All Ages

Sex: Females

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Year and Race Options: 2018-2023 by Single Race

Suicide by Means Among Males, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Fatal Injury Reports

Injury Outcome: Fatal

Injury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: All Ages

Sex: Males

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Year and Race Options: 2018-2023 by Single Race

Suicide by Means, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Fatal Injury Reports

Injury Outcome: Fatal

Injury Type: All Injury

Data Years: 2023

Geography: United States

Intent: Suicide

Mechanism: All Injury

Age: All Ages

Sex: All Sexes

Race: All Races

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Metro/Non-Metro Indicator: None Selected

YPLL Age: 65

Year and Race Options: 2018-2023 by Single Race

Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Plans and Attempts Among High School Youth, 2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2025). 1991-2023 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. Available at http://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/.

Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Plans and Attempts by Sex, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ Tables 6.71B, 6.72B, 6.73B

Self-Reported Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Plans and Attempts by Age, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table 6.70B

Self-Reported Suicide Plans and Attempts, 2021-2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2023). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2021 (NSDUH-2021-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table 6.71A

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2023). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2022 (NSDUH-2022-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table 6.68A

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2024). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2023 (NSDUH-2023-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table 6.68A

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Tables 6.71A, 6.72A, 6.73A

Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Plans, Attempts, and Deaths, 2024

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2025). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2024 (NSDUH-2024-DS001). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

Table: 6.70A

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: Year; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Ten Leading Causes of Death by Age, 2023

Under the age of 1

- Congenital Anomalies (4,005)

- Short Gestation (2,922)

- SIDS (1,445)

- Unintentional Injury (1,291)

- Maternal Pregnancy Complications (1,141)

- Bacterial Sepsis (621)

- Placental Cord Membranes (569)

- Respiratory Distress (449)

- Intrauterine Hypoxia (365)

- Circulatory System Disease (356)

Ages 1-4

- Unintentional Injury (1,275)

- Congenital Anomalies (426)

- Homicide (275)

- Malignant Neoplasms (269)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (142)

- Heart Disease (131)

- Septicemia (68)

- Perinatal Period (54)

- Cerebrovascular (53)

- COVID-19 (44)

Ages 5-9

- Unintentional Injury (684)

- Malignant Neoplasms (387)

- Congenital Anomalies (210)

- Homicide (187)

- Heart Disease (77)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (67)

- Septicemia (52)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (46)

- Cerebrovascular (37)

- COVID-19 (26)

Ages 10-14

- Unintentional Injury (914)

- Suicide (481)

- Malignant Neoplasms (463)

- Homicide (338)

- Congenital Anomalies (192)

- Heart Disease (96)

- Cerebrovascular (66)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (58)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (48)

- Diabetes Mellitus (35)

Ages 15-24

- Unintentional Injury (14,126)

- Suicide (5,936)

- Homicide (5,745)

- Malignant Neoplasms (1,463)

- Heart Disease (835)

- Congenital Anomalies (443)

- Diabetes Mellitus (259)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (219)

- Cerebrovascular (162)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (157)

Ages 25-34

- Unintentional Injury (30,163)

- Suicide (8,453)

- Homicide (5,828)

- Malignant Neoplasms (3,503)

- Heart Disease (3,474)

- Liver Disease (1,626)

- Diabetes Mellitus (1,110)

- Cerebrovascular (579)

- Complicated Pregnancy (522)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (458)

Ages 35-44

- Unintentional Injury (36,159)

- Heart Disease (11,528)

- Malignant Neoplasms (11,291)

- Suicide (8,533)

- Liver Disease (5,013)

- Homicide (4,487)

- Diabetes Mellitus (2,604)

- Cerebrovascular (2,057)

- Septicemia (987)

- Influenza and Pneumonia (967)

Ages 45-54

- Malignant Neoplasms (32,867)

- Unintentional Injury (30,559)

- Heart Disease (30,430)

- Liver Disease (8,866)

- Suicide (7,653)

- Diabetes Mellitus (6,653)

- Cerebrovascular (5,364)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (2,641)

- Homicide (2,571)

- Nephritis (2,442)

Ages 55-64

- Malignant Neoplasms (101,714)

- Heart Disease (79,726)

- Unintentional Injury (33,710)

- Diabetes Mellitus (15,958)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (15,748)

- Liver Disease (14,764)

- Cerebrovascular (13,425)

- Suicide (7,816)

- Nephritis (6,196)

- Septicemia (5,665)

Ages 65+

- Heart Disease (554,413)

- Malignant Neoplasms (461,345)

- Cerebrovascular (140,813)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (125,603)

- Alzheimer’s Disease (112,548)

- Unintentional Injury (73,804)

- Diabetes Mellitus (68,550)

- Nephritis (45,200)

- COVID-19 (44,097)

- Parkinson’s Disease (39,238)

All Ages

- Heart Disease (680,981)

- Malignant Neoplasms (613,352)

- Unintentional Injury (222,698)

- Cerebrovascular (162,639)

- Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (145,357)

- Alzheimer’s Disease (114.034)

- Diabetes Mellitus (95,190)

- Nephritis (55,253)

- Liver Disease (52,222)

- COVID-19 (49,932)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]) Available from URL: www.wisqars.cdc.gov

Leading Causes of Death

Ages: 1-14 in 5-year groups; 15-65+ in 10-year groups

Ethnicity: All Ethnicities

Geographies: United States

Intent: All Deaths with drilldown to ICD codes

Number: 10

Race: All Races

RaceYear: 2018-2021 by Single Race

Sexes: All Sexes

Years: 2023

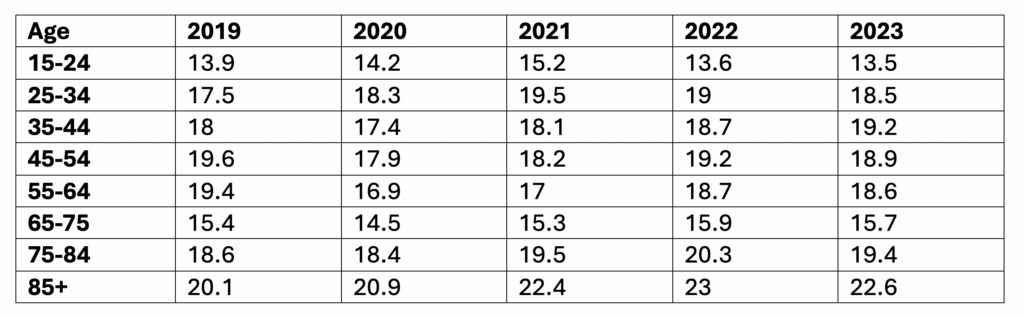

Suicide Rates by Age, 2019-2023

Crude rate per 100,000

Source: CDC, 2024

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year, Ten-Year Age Groups

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

County-Level Suicide Death Rates, 2019 to 2023, Continued

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: State; County

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

County-Level Suicide Death Rates, 2019-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: State; County

Show Totals: Disabled

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Versus Homicide Rates, 2014-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm); X85-Y09 (Assault)

Year/Month 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: Year; ICD Sub-Chapter

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm); X85-Y09 (Assault)

Group By: Year; ICD Sub-Chapter

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Suicide Rates by Sex, 2014-2023

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020

Group By: Year; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Group By: Year; Sex

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except

Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

Hispanic Origin: Not Hispanic or Latino

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Single Race 6

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except Infant Age Groups)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018-2023 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2024. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2023, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

ICD-10 Codes: X60-X84 (Intentional self-harm)

Year/Month: 2019; 2020; 2021; 2022; 2023

Group By: Year; Hispanic Origin

Show Totals: True

Show Zero Values: False

Show Suppressed: False

Standard Population: 2000 U.S. Std. Population

Calculate Rates Per: 100,000

Rate Options: Default intercensal populations for years 2001-2009 (except Infant Age Groups)

Request Technical Assistance

If you are seeking individualized suicide prevention training and support, please fill out our Contact Us form.

The Puerto Rico Department of Health (PRDoH)’s Commission on Suicide Prevention, which receives funding from the CDC Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Program, has implemented a Media Monitoring and Recommendation Initiative to ensure that suicide-related news coverage adheres to ethical standards while promoting awareness and prevention resources. Recognizing the critical role of the media in shaping public perception, the PRDoH proactively monitors local media, as well as social media platforms, to identify harmful reporting practices and provide constructive feedback.

Through regular communication with journalists, editors, and digital content creators, the PRDoH provides evidence-based recommendations on suicide reporting and recognizes media outlets that adhere to best practices to reinforce positive reporting behavior. In addition, the PRDoH builds media capacity through its free online course for journalists and content creators, called “The Role of Media in Suicide Prevention.” Some results of these efforts include:

• Articles featuring safer images, such as depicting a helpline instead of including a photo of the deceased

• A shift to safer content, such as a brief note of a death being investigated as a suicide rather than graphic descriptions of method

• Inclusion of the 988 Lifeline

• Replacing stigmatizing language with appropriate language (such as “died by suicide”)

• Improved media relationships

• Broader public exposure to the 988 Lifeline

Although time consuming, these efforts have helped build trust with local media outlets. By reaching out directly to journalists, being consistent with guidelines, and providing suicide data and local resources for the media to share, the PRDoH has created positive shifts to promote help-seeking behavior and increase suicide prevention awareness in Puerto Rico.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) Preventing Suicide in Michigan Men Program, funded by the CDC’s Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Grant program, uses communication strategies that incorporate suicide-centered lived experience perspectives and promote the use of safe messaging. As part of this program, in 2022 MDHHS created and disseminated a paid media campaign intended to increase help-seeking behaviors among adult men in Michigan through storytelling. The campaign was created with the participation of three Michigan men with suicide-centered lived experience whose stories were featured in the campaign. It focuses on hope and resilience and encourages men to reach out for help. The tagline of the campaign is: “Speak up. The life you save could be your own.”

In 2023 MDHHS partnered with the developers of the Tool for Evaluating Media Portrayals of Suicide (TEMPOS) and individuals from the University of Michigan to host safe messaging training webinars. Over 150 media and public health professionals attended the events. On post-webinar evaluation surveys, 90% of respondents said the webinar increased their understanding of the risks associated with communications about mental health and suicide and 93% said that they were very likely or somewhat likely to use the TEMPOS tool in the future.

Never a Bother, the California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) youth suicide prevention campaign, was launched in the spring of 2024. By the end of that year, it had garnered over 726 million overall campaign views. The campaign takes a youth-centered approach and employs strategies for effective youth engagement and co-creation. Never a Bother combines traditional media efforts (billboards, commercials, outreach materials) with grants to youth-serving community-based organizations and Tribal entities. These grants are intended to foster the use of evidence-informed and community-based suicide prevention strategies. This model engages trusted community messengers to amplify and reinforce the campaign’s messages at the local level.

Using focused, safe, positive, and community specific messaging, combined with stories from youth with suicide-centered lived experience, the campaign seeks to increase awareness and use of resources, services, and supports, while offering hope to those who need it most. The Never a Bother website has resources for both youth and caregivers about how to support youth before, during, and after a crisis, including postvention communication resources. The campaign website and the campaign’s Instagram and YouTube channels also showcase stories from youth and caregivers, as well as videos on safe messaging and what happens when you call 988. These efforts help ensure the campaign is customized by and for different communities and further extend Never a Bother’s messaging, reach, and impact.

Washington’s House Bill 2315 requires suicide prevention continuing education at differing levels of depth for all mental health and health professionals, ranging from social workers to chiropractors to dentists. The Washington State Department of Health (WSDH) maintains a list of suicide-specific CEU requirements for the different professions, as well as a list of approved training opportunities that professionals can choose from to obtain CEUs. Only trainings reviewed and confirmed as meeting WSDH’s preset minimum education standards are included in the list.

Pennsylvania’s Act 71/House Bill 1559 requires all school districts to create and implement suicide prevention policies and provide four cumulative hours of suicide prevention training for all 6-12th grade educators every five years. To support schools in meeting this requirement, Pennsylvania developed a variety of free online courses that are available on Prevent Suicide PA’s Online Learning Center. Several of these trainings were developed specifically for educators. There are continuous efforts to expand course offerings to address specific risk factors, overview interventions and treatment approaches, and highlight the needs of populations at increased risk. Additionally, Pennsylvania has worked to maintain an updated list of trainings that schools may consider to help meet the state’s requirements.

South Carolina’s Code of Law Section 59-26-110requires all middle and high school educators to participate in two hours of suicide prevention continuing education for credential renewal. To help school educators meet this requirement, the South Carolina Department of Education’s Office of Educator Effectiveness and Leadership Development (OEELD) partnered with the South Carolina chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) to offer the More Than Sad program. The OEELD helps to promote More Than Sad opportunities and the South Carolina AFSP chapter offers schools free trainings-for-trainers through an agreement with the South Carolina Youth Suicide Prevention Initiative.

California passed Assembly Bill 2246 in 2016, which requires grade 7-12 public schools to develop and implement comprehensive suicide prevention policies, including guidance on suicide prevention training for teachers. The bill also includes language that requires the state to provide funding to support suicide prevention policies and training in public schools. After the bill passed, former Governor Jerry Brown approved the 2018–19 state budget, which designated $1.7 million to the Department of Education to cover the cost of suicide prevention training. More recently, the Department of Education has collaborated with mental health professionals, including the Student Mental Health Policy Workgroup, to provide a Model Youth Suicide Prevention Policy.

The Indiana Division of Mental Health and Addiction (DMHA) provides the state’s local suicide prevention coalitions with a suicide prevention planning tool that offers guidance on working with partners, assessing communities, action planning, and engaging the media. To further support local coalitions, Indiana contracted with Mental Health America of Indiana’s Indiana Suicide Prevention Network (ISPN) to fund a director role responsible for managing and maintaining the ISPN, providing technical assistance support to local coalitions, and disseminating the state suicide prevention plan and framework to partners and communities.

Indiana funded the full-time ISPN director role through Indiana’s Mental Health Block Grant to meet the state’s need for sustainable systems infrastructure to support suicide prevention efforts. The DMHA also contracted with Education Development Center to coordinate statewide suicide prevention infrastructure plans that further support public and private buy-in adoption of the state suicide prevention plan and efforts.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission partners with the Texas Suicide Prevention Collaborative to support the efforts of a statewide suicide prevention council as well as the state’s regional suicide prevention coalitions. The collaborative provides ongoing support to these regional coalitions via trainings, website maintenance, toolkits, one-pagers, and more. These supports increase statewide capacity to consistently and effectively implement suicide prevention strategies at the local level.

The Ohio Suicide Prevention Foundation (OSPF) conducts frequent surveys, community listening sessions, focus groups, and needs assessments with Suicide Prevention Coalitions, L.O.S.S. Teams, and other community-level partners in the state to understand the local needs of people at risk for suicide. These activities track growth in coalitions, L.O.S.S. Teams, and communities to gather information about strategies being implemented and areas that require intervention and collaboration.

OSPF also regularly hosts learning opportunities focused on suicide prevention and strategic planning topics that align with expressed needs. All OSPF efforts take a quality improvement and quality assurance approach to comprehensive suicide prevention. Additionally, the Suicide Prevention Plan for Ohio’s Implementation Team ensures that all initiatives, demographic groups, and communities receive evaluation supports at the state and local levels.

In 2023, the Missouri Department of Mental Health worked closely with Partners in Prevention and Education Development Center to facilitate the first ever Suicide Prevention Coalition Academy in the United States. The academy was designed to provide guidance to community coalitions on implementing sustainable, evidence-based suicide prevention efforts using the newly developed Community-Led Suicide Prevention Toolkit. The academy included a two-day, in-person event followed by virtual community of practice sessions each month for a year. The academy objectives were aimed at providing coalitions with the information and skills to successfully adopt or expand suicide prevention efforts, assisting coalitions in developing and implementing strategic plans, and creating collaborations among community coalitions and other agencies to provide mentorship and support. A similar academy is being planned for the near future.

The South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH) offers services through 16 community mental health centers, clinics, inpatient psychiatric hospitals, a substance use treatment facility, a community nursing care center, and three nursing homes for veterans. SCDMH provided these health systems with sample policies to support implementation and tracking of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) through electronic health records. While implementation of the C-SSRS is not legislatively mandated, SCDMH monitors C-SSRS use via electronic record review to ensure that all patients who enter a publicly funded center are screened for suicide risk.

Each year, the North Carolina Division of Public Health (NCDPH), Injury and Violence Prevention Branch submits suicide prevention strategies to the NCDPH Healthy Communities Program to be implemented by county health departments. Each year, the local health departments must select and implement at least two chronic disease and injury prevention strategies related to different topics, which may include suicide prevention. Health departments that implement suicide prevention strategies are required to host at least one of four suicide prevention gatekeeper trainings: Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM), Mental Health First Aid (MHFA), or Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) for community-based agencies in their districts. To make suicide prevention programs more accessible, North Carolina inventoried programs in the state that are involved in suicide prevention and created a searchable public-facing map. Programs can submit their names for inclusion on the map online.